Simple Solutions: Ergonomics for Construction Workers

Summary Statement

Booklet and access to individual tip sheets that contain practical ideas to help reduce the risk of repetitive stress injury in common construction tasks including floor and ground-level work, overhead work, material handling, and hand-intensive work.

2007

Table of Contents

Foreword

Why This Booklet?

Oh, My Aching Body!

What Is Ergonomics?

Simple Solutions for Floor and Ground-Level Work

- Introduction

- TIP SHEET #1 Fastening Tools that Reduce Stooping

- TIP SHEET #2 Motorized Concrete Screeds

- TIP SHEET #3 Rebar-Tying Tools

- TIP SHEET #4 Kneeling Creepers

- TIP SHEET #5 Adjustable Scaffolding for Masonry Work

Simple Solutions for Overhead Work

- Introduction

- TIP SHEET #6 Bit Extension Shafts for Drills and Screw Guns

- TIP SHEET #7 Extension Poles for Powder-Actuated Tools

- TIP SHEET #8 Spring-Assisted Drywall Finishing Tools

- TIP SHEET #9 Pneumatic Drywall Finishing Systems

Simple Solutions for Lifting, Holding, and Handling Materials

- Introduction

- TIP SHEET #10 Lightweight Concrete Block

- TIP SHEET #11 Pre-Blended Mortar and Grout Bulk Delivery Systems

- TIP SHEET #12 Skid Plates to Move Concrete-Filled Hoses

- TIP SHEET #13 Vacuum Lifters for Windows and Sheet Materials

Simple Solutions for Hand-Intensive Work

- Introduction

- TIP SHEET #14 Ergonomic Hand Tools

- TIP SHEET #15 Easy-Hold Glove for Mud Pans

- TIP SHEET #16 Power Caulking Guns

- TIP SHEET #17 Reduced Vibration Power Tools

- TIP SHEET #18 Power Cleaning and Reaming with a Brush

- TIP SHEET #19 Snips for Cutting Sheet Metal

- TIP SHEET #20 Quick-Threading Lock Nuts

Ordering Information

To receive documents or other information about occupational safety and health topics, contact NIOSH at:

NIOSH—Publications Dissemination

4676 Columbia Parkway

Cincinnati, OH 45226-1998

Phone: (800) CDC-INFO (232-4636)

TTY: (888) 232-6348

E-mail: cdcinfo@cdc.gov

Website: www.cdc.gov/niosh

For a monthly update on news at NIOSH, subscribe to NIOSH eNews by visiting

www.cdc.gov/niosh/eNews.

NIOSH is a federal government research agency that works to identify the causes of work-related diseases and injuries, evaluate the hazards of new technologies and work practices, and create ways to control these hazards so that workers are protected.

DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2007–122, August 2007.

Acknowledgments

Writing and Research

James T. Albers, NIOSH Division of Applied Research and Technology

Cheryl F. Estill, NIOSH Division of Surveillance, Hazard Evaluations, and Field Studies

Editing and Design

Eugene Darling, Labor Occupational Health Program (LOHP), University of California, Berkeley

Kate Oliver, LOHP

Laura Stock, LOHP

Anne Votaw, NIOSH

Illustrations

Mary Ann Zapalac

Photo Credits

All photos: NIOSH, except: p.23 (bottom) Jennifer Hess; p.27 (both photos) Earl Dotter; p.29 (bottom) Racatac Industries Inc.; p.31 (both photos) Non-Stop Scaffolding; p.35 (left) Genie Industries, (right) Scott Schneider; p.37 (bottom) Streimer Sheet Metal Works, Inc.; p.39 (bottom) Hilti Corporation; p.41 (top) Midstate Education and Service Foundation, (bottom) Tape Tech Tools; p.43 (both photos) Midstate Education and Service Foundation; p.49 (bottom) Expanded Shale, Clay, and Slate Institute; p.51 (top) Messer Construction, (bottom) Spec Mix Inc.; p.53 (top) Scott Fulmer, (middle/bottom) Jennifer Hess; p.55 (top) Wood’s Powr-Grip; p.59 Cal/OSHA; p.61 (all photos) Cal/OSHA; p.63 (all photos) Midstate Education and Service Foundation; p.65 (bottom) Quickpoint, Inc.; p.67 (bottom) ErgoAir, Inc.; p.69 (top) Messer Construction; p.71 (middle/bottom) Midwest Tool and Cutlery Co.; p.73 (bottom) Slip-On Lock Nut Co. and Morton Machine Works.

Tip Sheet Contributors

Tip Sheet #1. Jim Albers, MPH, CIH, NIOSH, Cincinnati, OH, and Cherie Estill, MS, PE, NIOSH, Cincinnati, OH.

Tip Sheet #2. Scott Schneider, MS, CIH, Laborers’ Health and Safety Fund of North America, Washington, DC, and Jim Albers, MPH, CIH, NIOSH, Cincinnati, OH.

Tip Sheet #3. Jennifer Hess, DC, PhD, University of Oregon Labor Education and Research Center, Eugene, OR, and Jim Albers, MPH, CIH, NIOSH, Cincinnati, OH.

Tip Sheet #4. Kate Stewart, MS, and Steve Russell, MS, Seattle, WA, and Build It Smart, Olympia, WA.

Tip Sheet #5. Peter Vi, MS, Construction Safety Association of Ontario, Etobicoke, Ontario, Canada, and Jim Albers, MPH, CIH, NIOSH, Cincinnati, OH.

Tip Sheet #6. Phil Lemons and Kelly True, Streimer Sheet Metal, Portland, OR, and Jim Albers, MPH, CIH, NIOSH, Cincinnati, OH.

Tip Sheet #7. Charles P. Austin, MS, CIH, Sheet Metal Occupational Health Institute Trust (SMOHIT), Alexandria, VA.

Tip Sheet #8. Greg Shaw, Midstate Education and Service Foundation, Ithaca, NY.

Tip Sheet #9. Greg Shaw, Midstate Education and Service Foundation, Ithaca, NY.

Tip Sheet #10. Dan Anton, PhD, PT, ATC, University of Iowa, College of Public Health, Department of Occupational and Environmental Health, Iowa City, IA.

Tip Sheet #11. Pamela Entzel, JD, MPH, Center to Protect Workers’ Rights, Silver Spring, MD, Jim Albers, MPH, CIH, NIOSH, Cincinnati, OH, and Cherie Estill, MS, PE, NIOSH, Cincinnati, OH.

Tip Sheet #12. Jennifer Hess, DC, PhD, University of Oregon Labor Education and Research Center, Eugene, OR, and the Center to Protect Workers’ Rights, Silver Spring, MD.

Tip Sheet #13. Jim Albers, MPH, CIH, NIOSH, Cincinnati, OH, and Cherie Estill, MS, PE, NIOSH, Cincinnati, OH.

Tip Sheet #14. Adapted from the booklet Easy Ergonomics: A Guide to Selecting Non-Powered Hand Tools (2004), a joint publication of the California Dept. of Occupational Safety and Health (Cal/OSHA) and NIOSH. Cincinnati, OH: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No.2004-164.

Tip Sheet #15. Greg Shaw, Midstate Education and Service Foundation, Ithaca, NY.

Tip Sheet #16. Jim Albers, MPH, CIH, NIOSH, Cincinnati, OH, and Cherie Estill, MS, PE, NIOSH, Cincinnati, OH.

Tip Sheet #17. Jim Albers, MPH, CIH, NIOSH, Cincinnati, OH, and Cherie Estill, MS, PE, NIOSH, Cincinnati, OH.

Tip Sheet #18. Jim Albers, MPH, CIH, NIOSH, Cincinnati, OH, and Cherie Estill, MS, PE, NIOSH, Cincinnati, OH.

Tip Sheet #19. Charles P. Austin, MS, Sheet Metal Occupational Health Institute Trust (SMOHIT), Alexandria, VA, Jim Albers, MPH, CIH, NIOSH, Cincinnati, OH, and Cherie Estill, MS, PE, NIOSH, Cincinnati, OH.

Tip Sheet #20. Jim Albers, MPH, CIH, NIOSH, Cincinnati, OH, and Cherie Estill, MS, PE, NIOSH, Cincinnati, OH.

Reviewers

NIOSH wishes to acknowledge the following early reviewers of this document. Reviewers’ organizations are listed for identification only. While their suggestions have improved the quality of the material, the authors accept full responsibility for the content: Tom Alexander (Independent Electrical Contractors, National Safety Committee), Tony Barsotti, CSP (Temp-Control Mechanical Corporation), Bruce Bowman, PE (Independent Electrical Contractors, National Safety Committee), Stephen Hecker, PhD (University of Washington-Seattle), Ira Janowitz, MS, CPE (Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory), Rashod Johnson, PE (Masonry Contractors Association of America), Phil Lemons, CSP (Streimer Sheet Metal), John Masarick (Independent Electrical Contractors), Mike McCullion, CSP (Sheet Metal and Air Conditioning Contractors National Association), Jim McGlothlin, PhD, CPE (Purdue University), Gary Mirka, PhD (Iowa State University), Brian L. Roberts, CSP, CIE (Independent Electrical Contractors), Kristy Schultz, MS, CIE (California State Compensation Insurance Fund).

Construction is a physically demanding occupation, but a vital part of our nation and the U.S. economy. In 2006, the total annual average number of workers employed in construction rose to an all-time high of nearly 7.7 million, according to U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data. This large workforce handled tasks that range from carrying heavy loads to performing repetitive tasks, placing them at risk of serious injury. The physically demanding nature of this work helps to explain why injuries, such as strains, sprains, and work-related musculoskeletal disorders, are so prevalent and are the most common injury resulting in days away from work.

Although the construction industry presents many workplace hazards, there are contractors in the U.S. who are successfully implementing safety and health programs to address these issues, including work-related musculoskeletal disorders.

The safety and health of all workers is a top priority for NIOSH. This booklet is intended to aid in the prevention of common job injuries that can occur in the construction industry.

The solutions in this booklet are practical ideas to help reduce the risk of repetitive stress injury in common construction tasks. While some solutions may need the involvement of the building owner or general contractor, there are also many ideas that individual workers and supervisors can adopt.

There are sections on floor and ground-level work, overhead work, material handling, and handintensive work. For each type of work, "simple solutions" for various tasks are described in a series of "Tip Sheets." The solutions consist mostly of materials or equipment that can be used to do the job in an easier way. Each Tip Sheet describes a problem, one possible solution, its benefits to the worker and employer, how much it costs, and where it can be purchased. All these solutions are readily available and are actually in use today in the U.S. construction industry.

We encourage both contractors and workers to consider the "simple solutions" in this booklet and look for ways you can adapt them to your own job and worksite.

John Howard, M.D.

Director

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

This booklet is intended for construction workers, unions, supervisors, contractors, safety specialists, human resources managers-anyone with an interest in safe construction sites. Some of the most common injuries in construction are the result of job demands that push the human body beyond its natural limits.Workers who must often lift, stoop, kneel, twist, grip, stretch, reach overhead, or work in other awkward positions to do a job are at risk of developing a work-related musculoskeletal disorder (WMSD). These can include back problems, carpal tunnel syndrome, tendinitis, rotator cuff tears, sprains, and strains.

To aid in the prevention of these injuries, this booklet suggests many simple and inexpensive ways to make construction tasks easier, more comfortable, and better suited to the needs of the human body.

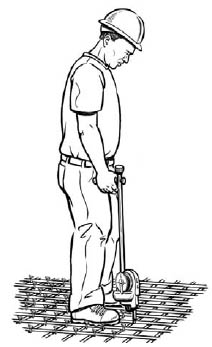

Example of a "simple solution." This ironworker uses a tool that automatically ties rebar with the pull of a trigger. The extended handle lets him work while standing upright. No leaning, kneeling, stooping, or hand twisting are necessary.

- Construction is one of the most hazardous industries in the United States.

- The number of back injuries in U.S. construction was 50% higher than the average for all other U.S. industries in 1999 (CPWR, 2002).

- Backaches and pain in the shoulders, neck, arms, and hands were the most common symptoms reported by construction workers in one study (Cook et al, 1996).

- Material handling incidents account for 32% of workers' compensation claims in construction, and 25% of the cost of all claims. The average cost per claim is $9,240 (CNA, 2000).

- Musculoskeletal injuries can cause temporary or even permanent disability, which can affect the worker's earnings and the contractor's profits

The "Tip Sheets" in this booklet show how using different tools or equipment may reduce the risk of injury. All of the items described in this booklet have been used on working construction sites. Given the nature of construction, some solutions here may not be appropriate for all worksites. Sometimes solutions discovered for one trade can be modified for other trades.

This booklet provides general information regarding the methods some construction contractors have used to reduce workers' exposures to risk factors for work-related musculoskeletal disorders. The examples described in this booklet may not be appropriate for all types of construction work. The use of the tools and equipment described in the booklet does not ensure that a musculoskeletal disorder will not occur. The information contained in this booklet does not produce new obligations or establish any specific standards or guidelines.

Our goal has been to describe solutions that are also cost-effective. Although the cost of some of the solutions here exceeds $1,000, which may be too high for some contractors, we believe successful implementation will lead to a quick recovery of the investment in many cases.

Construction work is hard work, and construction workers feel the results. In one survey, seven out of ten construction workers from 13 trades reported back pain, and nearly a third went to the doctor for it (Cook et al, 1996).

Back pain, carpal tunnel syndrome, tendinitis, rotator cuff syndrome, sprains, and strains are types of musculoskeletal disorders. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSDs) are caused by job a ctivities and conditions, like lifting, repetitive motions, and work in confined areas. All of these are part of construction work. WMSDs can become long-term, disabling health problems that keep you from working and enjoying life. Not only do these injuries hurt your body, but they can reduce your earnings and your employer's profit.

You have an increased risk of these injuries if you often:

- Carry heavy loads

- Work on your knees

- Twist your hands or wrists

- Stretch to work overhead

- Use certain types of tools

- Use vibrating tools or equipment.

On top of that, tight deadlines mean a fast pace. Pushing the pace increases your risk even more.

A study of workers' compensation claims filed in Washington State between 1990-98 reported that the highest risks for developing a WMSD were "in industries characterized by manual handling and forceful repetitive exertions." According to the study, construction work accounted for 10 of the top 25 sectors in need of interventions to prevent neck, back, and upper extremity WMSDs (Silverstein, 1998).

One insurance company reported that 29% of insured mechanical and electrical contractors' workers' compensation claims were due to WMSDs. A quarter of those claims resulted in temporary or permanent disability. The insurer also reported that WMSD claims for electrical contractors average around $6,600 for each WMSD, while the average claim for a mechanical contractor was around $7,300 (NIOSH 2006).

Many people in construction believe that sprains and strains are just the nature of the business. But new tools and materials are now available that can make work less risky and increase productivity. This booklet shows some of the solutions, large and small, to WMSDs.

As you read this booklet, the solutions may or may not apply to your specific jobsite or trade. You will need to review cost, quality, and site-specific information to make sure that the solution will meet your needs. Also, these ideas can be adapted. Notice the principles involved: What kinds of activities are most likely to cause injuries? How can they be minimized?

Sometimes a small change in tools, equipment, or materials can make a big difference in preventing injuries. We wish you the best as you strive to make improvements to the work you do and your worksite.

NIOSH believes that better work practices and tools can reduce the frequency and seriousness of sprains and strains among construction workers. These suggestions can be adapted for your own jobsite. SAFER - HEALTHIER - PEOPLE™ |

The goal of the science of ergonomics is to find a "best fit" between the worker and the job conditions. Ergonomics tries to come up with solutions to make sure workers stay safe, comfortable, and productive. Ergonomics is a new topic for the construction industry, but the ideas have been around for many years. For example, in 1894 the split-level scaffold was designed for masonry work in the U.S. to reduce workers' frequent bending. This new scaffold system was designed to increase workers' productivity by reducing the time spent in awkward positions. There is still a strong case for using ergonomic improvements both to reduce workers' exposure to risk factors for WMSDs and to improve their productivity.

Ergonomics looks at how:

|

Are directly related to ... |

|

Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorder

Work-related musculoskeletal disorders (WMSDs)are the leading cause of disability for people in their working years. They can be caused by frequently working in a way that puts stress on the body as such:

- Gripping

- Kneeling

- Lifting

- Working in awkward positions

- Applying force

- Repeating movements

- Bending

- Working overhead

- Twisting

- Using vibrating equipment

- Sqatting

- Over-reaching

The best way to reduce WMSDs is to use the principles of ergonomics to redesign tools, equipment, materials, or work processes.

Simple changes can make a big difference. Using ergonomic ideas to improve tools, equipment, and jobs reduces workers' contact with those factors that can result in injury. When ergonomic changes are introduced into the workplace or job site, they should always be accompanied by worker training on how to use the new methods and equipment, and how to work safely.

Do You Need an Ergonomics Program?Many ergonomics experts recommend that employers and joint labor-management groups develop their own ergonomics programs to analyze risk factors at the worksite and find solutions. These programs may operate as part of the site's health and safety program, or may be separate. An ergonomics program can be a valuable way to reduce injuries, improve worker morale, and lower workers' compensation costs. Often, these programs can also increase productivity.

There may be a particularly urgent need for an ergonomics program at your site if:

- Injury records or workers' compensation claims show excessive hand, arm, and shoulder problems; low back pain; or carpal tunnel syndrome.

- Workers often say that some tasks are causing aches, pains, or soreness, especially if these symptoms do not go away after a night's rest.

- There are jobs on the site that require forceful actions, movements that are repeated over and over, heavy lifting, overhead lifting, use of vibrating equipment, or awkward positions such as raising arms, bending over, or kneeling.

- Other businesses similar to yours have high rates of work-related musculoskeletal disorders.

- Trade magazines or insurance publications in your industry frequently cover these disorders.

Effective ergonomics programs have included the following elements:

- Employer commitment of time, personnel, and resources

- Someone in charge of the program who is authorized to make decisions and institute change

- Active employee involvement in identifying problems and finding solutions

- A clearly defined administrative structure (such as a committee)

- A system to identify and analyze risk factors

- A system to research, obtain, and implement solutions such as new equipment

- Worker and management training

- Medical care for injured workers

- Maintaining good injury records

- Regular evaluation of the program's effectiveness.

Education and training programs have been developed for construction general contractors by the Associated General Contractors, the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners, the Sheet Metal Occupational Health Institute, and the Laborers' Union. Although the problems and solutions described in these organizations' materials may be specific to a sector or trade, you may find them useful when developing your own ergonomics program.

For additional information on developing an ergonomics program, see Elements of Ergonomics Programs (NIOSH Pub. No. 97-117) at www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/97-117.